The real solutions to reducing the impact of rising and volatile gasoline prices are more efficient cars and trucks, smarter growth, public transit, and vehicles that run on cleaner, alternative fuels, such as electricity. The latter is my area of expertise. My colleague, Anthony Swift, knows more about problems posing as solutions, including drilling for increasingly dirty sources of fossil fuels. In the article included below, he describes a new report which shows that the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline will actually increase domestic gasoline prices.

Anthony Swift is an attorney in the Natural Resources Defense Council’s International Program. This article first appeared on his Switchboard blog

One of the most misunderstood issues surrounding the proposed Keystone XL tar sands pipeline is its impact on U.S. gasoline prices. NRDC, Oil Change International and ForestEthics Advocacy released a report, Keystone XL: A Tar Sands PIpeline to Increase Oil Prices, today that take a close look at this complicated issue and evaluates Keystone XL’s impact on U.S. gasoline prices and supply. The study finds that Keystone XL is likely to both reduce the amount of gasoline produced in U.S. refineries for domestic markets and increase the cost of producing it, leading to even higher prices at the pump. Keystone XL’s supporters in the United States cite high gasoline prices as a reason to overlook the project’s tremendous environmental impacts and build the project. There are plenty of compelling reasons not to build the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline – it will expand a destructive extraction process, put our rivers, aquifers and lands at risk of tar sands oil spills, and would increase our dependence on tar sands – worsening climate change and undermining efforts to move to clean energy. In addition to this litany of problems, rather than decreasing U.S. oil and gasoline prices, the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline will lead to even more pain at the pump for American consumers.

So how does a pipeline increase gasoline prices?

First, Keystone XL is going divert crude oil from the Midwest, a region of the United States where refineries are designed to produce as much gasoline as possible from a barrel of oil, to the Gulf Coast of Texas, where refineries have reconfigured themselves to produce as much diesel as possible from a barrel of crude.

These differences are due to recent changes in the world market for oil and refined products. Historically gasoline commanded higher prices than diesel, driven largely by increasing U.S. consumption. That has changed over the last ten years as U.S. gasoline consumption has plateaued, due in large part to increasing automobile efficiency standards, and global demand for diesel continues to rise. Today, diesel commands a higher price than gasoline, particularly in the international market.

Gulf Coast refineries, which have access to lucrative international diesel markets, have taken advantage of these international trends by reconfiguring their operations to maximize diesel production. Meanwhile, Midwestern refineries, which do not have access to these international markets, have maintained their focus on the U.S. market. To give an example, refineries in the northern Midwest produce almost 22 gallons of gasoline from a barrel of oil, which refineries in the Texas Gulf only produce about 17 gallons. Moreover, refineries in the Texas Gulf are working with better quality crudes, crude which should produce more gasoline than the heavier, more sulfuric crudes processed in northern Midwestern refineries.

Right now, Canada doesn’t have ‘extra oil’ to put on Keystone XL. In fact there are nearly 2 million barrels a day of empty pipeline capacity available to export additional Canadian crude oil – Canada doesn’t produce enough oil to fill it. That means that in the short to medium term, Keystone XL will allow producers to send oil to the Gulf Coast instead of the Midwest. Simply sending 830,000 barrels of crude oil to Gulf Coast refineries instead of to Midwestern refineries will actually reduce the amount of gasoline produced by U.S. refineries by 80,000 barrels a day – that means about reducing the amount of gasoline available to U.S. consumers by about 1.2 billion gallons a year.

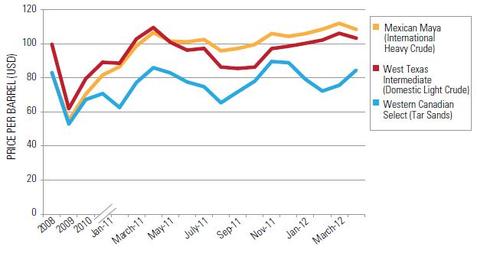

Second, Keystone XL will increase the cost of producing gasoline in the Midwest. Which TransCanada originally pitched Keystone XL to Canadian regulators in 2009, the company asserted that its pipeline would increase the price of Canadian tar sands. TransCanada argued that Canadian tar sands had historically sold on equal terms with Mexican heavy crude, but that increasing supplies in the Midwest had caused Canadian crude to sell at a $3 discount – a discount that Keystone XL would eliminate, increasing revenue to Canadian crude producers. In 2012, the discount for Canadian tar sands has increased to between $20 and $40 a barrel. Based on TransCanada’s earlier analysis, by eliminating that discount, Keystone XL would increase the cost of crude by up to $27 billion a year.

This wouldn’t matter for consumers if, as Keystone XL proponents often argue, Midwestern and Rocky Mountain refineries were just using the lower cost for crude to increase their profits. If that were the case, increasing the cost of oil by $20 to $40 a barrel would have little effect on consumers. The problem is, Midwestern refineries aren’t making significant profits. Even with after paying significantly discounted prices for crude oil, Midwestern refinery margins, or revenue per barrel refined, are less than Gulf Coast refineries, which pay significantly higher international prices for oil.

This is because Midwestern and Rocky mountain refineries don’t currently have access to more lucrative international diesel markets. If these refineries are forced to pay the higher international price of oil, they will be forced to cope the same way East Coast refineries have – by reducing their production, further decreasing U.S. gasoline supplies and increasing prices.

There are many reasons to argue that Keystone XL isn’t in the national interest. A closer examination of Keystone XL’s impact on U.S. oil and gasoline supplies provides one less reason to support the project.

Go here to read the full report.